DEM simulation of uniaxial testing in the EPT

DEM simulation of uniaxial testing in the EPT

Introduction

Over the years, as the popularity of the Discrete Element Method (DEM) has continued to grow, it has been increasingly used as a design tool. The accuracy of these models largely depends on the chosen DEM model and its parameters, and as pointed out in a post by David Curry (What numbers should I put in? The perennial question for DEM users) the adage of “garbage in – garbage out” holds true when carrying out DEM simulations. For cohesionless materials we have a range of parameters to account for - size, shape, stiffness and friction being some of the more commonly considered. But how many materials are truly cohesionless? Not many, so we end up having to add some additional parameters to our DEM simulations to account for the additional cohesive forces in the material. The origin of these cohesive forces and their respective mechanics vary from long and short range non-contact interaction forces, mechanical interlock, electrostatic forces, solid bridges and liquid bridges to name but a few.

So how does one go about capturing all of these phenomena in their DEM simulation? The first step is selecting a suitable contact model – a liquid bridge model is not much use for capturing the behaviour of fine particles in an electrostatic field. Provided you have negotiated that stage and selected a suitable contact model; you are then faced with the much more difficult proposition of model calibration.

Calibration

To some, “calibration” is a dirty word that simply means ‘cheating until you get the right answer’, but we can define it more concisely as “the process of adjusting physical modelling parameters in the computational model to improve agreement with experimental data” 1. Calibration isn’t a bad thing, it’s a necessary part of scientific life – we need to regularly calibrate our measuring instruments to ensure accuracy. Due to the assumptions we make in DEM; in relation to particle shape and number of particles we use to represent a system amongst other things; we need to calibrate our input parameters such that they provide a realistic result.

And much like the choice of contact model, the choice of calibration experiment is also important – you would not choose a quasi-static experiment to calibrate for a very dynamic regime as you may fail to capture much of the key behaviour such as impact dynamics. Obtaining suitable calibration data can be a challenge as one would like them to be both easily obtained and be highly repeatable.

The typical process of calibrating DEM contact model parameters involves tuning the observed response of the simulation to closely reproduce the macroscopic bulk behaviour measured in the calibration experiment. The mechanical behaviour of cohesive powders can be carefully measured using element tests such as biaxial test, true triaxial and hollow cylinder tests. However, in practice these tests can be expensive and slow to conduct and are rarely performed for industrial applications requiring material characterisation. More typically a test such as direct shear, ring shear, unconfined compression, triaxial compression or cone penetration is carried out.

The Case for Uniaxial Testers

For example, in industry the flow function of a cohesive solid is typically measured using either a ring shear tester or Jenike shear tester but these have some drawbacks. The Jenike test, whilst appearing to be quite straight forward is time consuming and can often be highly operator sensitive, both of which are problems when you want to have a high level of confidence in the result to use for calibration. Ring shear testers remove the operator sensitivity and repeatability problem by being highly automated, computer controlled devices but these can be very expensive to purchase and maintain. They also have particle size restrictions due to their small volume and may be limited to relatively low stress ranges which may not cover the range of interest.

Uniaxial testers offer an alternative method for characterising the flowability of powders and fine granular materials in industrial situations. Uniaxial testers apply a consolidation stress vertically and also apply the failure load vertically. This is appealing for two reasons: firstly it’s a mechanically simple device that’s easy to operate and secondly it’s physical similarity to the stress path associated with arching and the unconfined yield strength 2. One of the challenges with uniaxial testers is achieving a uniform level of consolidation throughout the depth of the sample, as wall friction can mean that the vertical stress in the sample at the bottom is significantly lower than the vertical stress applied at the top surface. To combat this there have been many designs considered over the years to deal this, each with their own strengths 3,4,5.

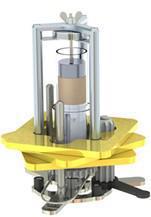

The University of Edinburgh had previous experience of developing successful uniaxial testers for large diameter particles 6. From this experience the Edinburgh Powder Tester (EPT) was developed for measuring the flowability of highly compressible, high value powders. While many previous efforts have focussed heavily on accurate laboratory measurement of unconfined yield strength, the Edinburgh testers aimed at speed, robustness and high repeatability for industrial use, with a close match to a Jenike cell being a secondary objective 2. The key differences between the Edinburgh Powder Tester and some previous devices lie in the attention to mechanical details for both the consolidation and failure load application and the strategic intent 2, which means the EPT offers repeatability results in the range of 5-10% relative standard deviation (RSD) for a vast range of materials 7, 8.

It is the simplicity and flexibility of uniaxial testers, coupled with a high level of repeatability, that make uniaxial testers ideal tools for calibrating DEM simulations of cohesive solids. For example, the EPT, which is a semi-automated uniaxial tester, can provide rapid measurements of various bulk mechanical properties of powders, including the stress–strain and the stress–porosity response during confined compression, the stress–strain response during unconfined compression including the peak unconfined strength and the caking strength over time consolidation, all of which can be utilised for calibrating you DEM simulation of a cohesive solid.

Recently, Freeman Technology; which has many years of experience of both powder testing and development of testing apparatus, including extensive knowledge of shear cells; entered into a highly productive collaboration with the University of Edinburgh, DuPont and The Chemours Company to develop a uniaxial powder tester for the commercial market that incorporates the key design elements of the EPT. The result of this collaboration is ‘The New Uniaxial Powder Tester from Freeman Technology’ which is a standalone uniaxial shear tester for powders, capable of testing a stress range of up to 100 kPa. The UPT comes in two versions: a manual version, which is ideally suited for quality control measurement in industrial situations and the advanced version with increased automation and reduction in operator inputs and advanced data logging capabilities which makes it very suitable as a DEM calibration tool for cohesive powders.

A DEM Example Case

At the University of Edinburgh, we have used uniaxial testers (EPT/UPT) extensively for calibrating DEM parameters for the Edinburgh Cohesion Model in EDEM 7,8,9,10,11,12 (which is currently available on the EDEM User forum and will be part of future versions of EDEM) due to the high level of repeatability and the flexibility to measure key properties quickly and easily in the laboratory.

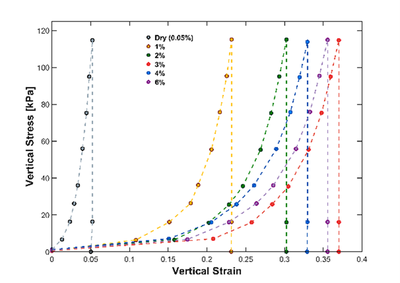

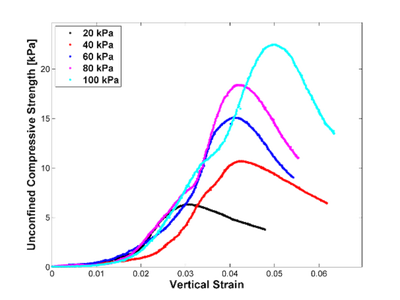

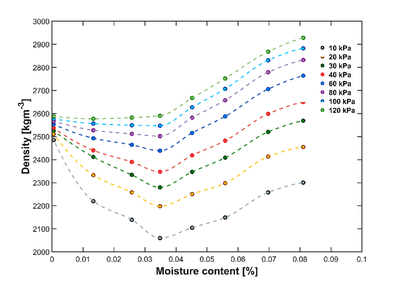

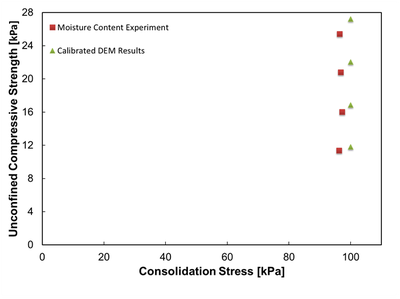

As an example, the measured stress-strain curves from the EPT for an iron ore solid at varying moisture contents (levels of cohesion) are shown in Figure 6 and Figure 7. A typical set of unconfined test results that make up a single uniaxial flow function (the peak strength vs. the consolidation stress) are shown for the same iron ore fines in Figure 8 for a single moisture content.

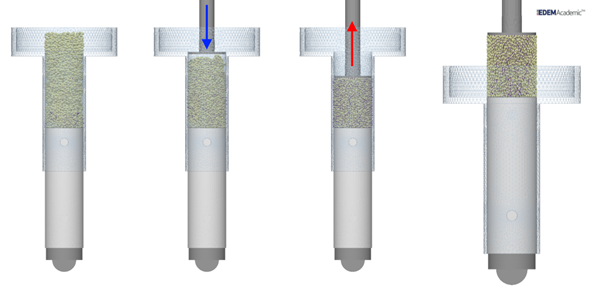

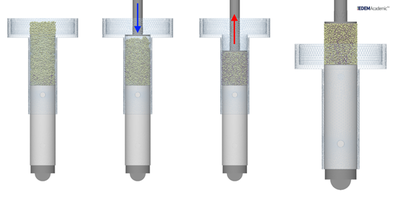

These measured values provide the range of various properties to be captured within the DEM simulation. A typical DEM simulation of a cohesive solid in the EPT is shown in Figure 9. The DEM simulation consists of the filling, confined compression, unloading of the sample and the crushing to failure of the unconfined sample.

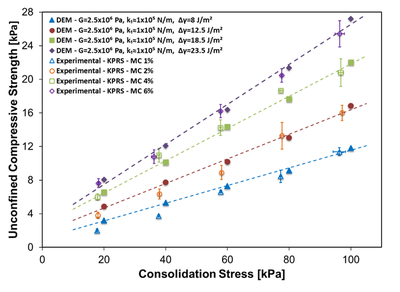

The measured properties provide the necessary information to define the loading stiffness, plasticity ratio and whether the material is exhibiting linear or non-linear stiffness, bulk density and level of cohesion to calibrate the DEM model. In order to capture the behaviour at different moisture contents, we need to calibrate the level of cohesion for each moisture content at one point on the flow function, as in Figure 10.

Once calibrated, it is possible capture the entire flow function spectrum for varying moisture contents with a good degree of accuracy, as shown in Figure 11, with the effect of moisture influencing only one model parameter i.e. the contact surface energy

This process provides a fully calibrated DEM model for cohesive powders for use in DEM simulations.

References

-

American Society of Mechanical Engineers., Guide for verification and validation in computational solid mechanics, American Society of Mechanical Engineers, 2006. https://www.asme.org/products/codes-standards/v-v-10-2006-guide-verification-validation (accessed July 13, 2017). ↩︎

-

T.A. Bell, E.J. Catalano, Z. Zhong, J.Y. Ooi, J.M. Rotter, Evaluation of the Edinburgh powder tester, in: PARTEC 2007 - Congr. Part. Technol., Nürnberg, 2007: pp. 1–6. http://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=en&btnG=Search&q=intitle:Evaluation+of+the+Edinburgh+Powder+Tester#0 (accessed October 5, 2013). ↩︎

-

L.P. Maltby, G.G. Enstad, Uniaxial Tester for Quality Control and Flow Property Characterization of Powders, Powder Handl. Process. 13 (1993) 135–139. ↩︎

-

M. Röck, M. Ostendorf, J. Schwedes, Development of an Uniaxial Caking Tester, Chem. Eng. Technol. 29 (2006) 679–685. doi:10.1002/ceat.200600068. ↩︎

-

R.E. Freeman, X. Fu, The Development of a Compact Uniaxial Tester, in: Part. Syst. Anal. 2011, Edinburgh, UK, 2011: pp. 1–6. ↩︎

-

Z. Zhong, J.Y. Ooi, J.M. Rotter, Predicting the handlability of a coal blend from measurements on the source coals, Fuel. 84 (2005) 2267–2274. doi:10.1016/j.fuel.2005.05.023. ↩︎

-

S.C. Thakur, H. Ahmadian, J. Sun, J.Y. Ooi, An experimental and numerical study of packing, compression, and caking behaviour of detergent powders, Particuology. 12 (2014) 2–12. doi:10.1016/j.partic.2013.06.009. ↩︎

-

J.P. Morrissey, Discrete Element Modelling of Iron Ore Fines to Include the Effects of Moisture and Fines, University of Edinburgh, 2013. https://www.era.lib.ed.ac.uk/handle/1842/8270. ↩︎

-

S.C. Thakur, J.P. Morrissey, J. Sun, J.F. Chen, J.Y. Ooi, Micromechanical analysis of cohesive granular materials using discrete element method with an adhesive elasto-plastic contact model, Granul. Matter. 16 (2014) 383–400. doi:10.1007/s10035-014-0506-4. ↩︎

-

S.C. Thakur, J.Y. Ooi, H. Ahmadian, Scaling of discrete element model parameters for cohesionless and cohesive solid, Powder Technol. (2015). doi:10.1016/j.powtec.2015.05.051. ↩︎

-

A. Janda, J.Y. Ooi, DEM modeling of cone penetration and unconfined compression in cohesive solids, Powder Technol. 293 (2016) 60–68. doi:10.1016/j.powtec.2015.05.034. ↩︎

-

J.P. Morrissey, J.Y. Ooi, J.F. Chen, K.T. Tano, G. Horrigmoe, Measurement and prediction of compression and shear behavior of wet iron ore fines, in: 7th World Congr. Part. Technol., Beijing, China, 2014: p. 8. ↩︎